Caregiver Kintsugi

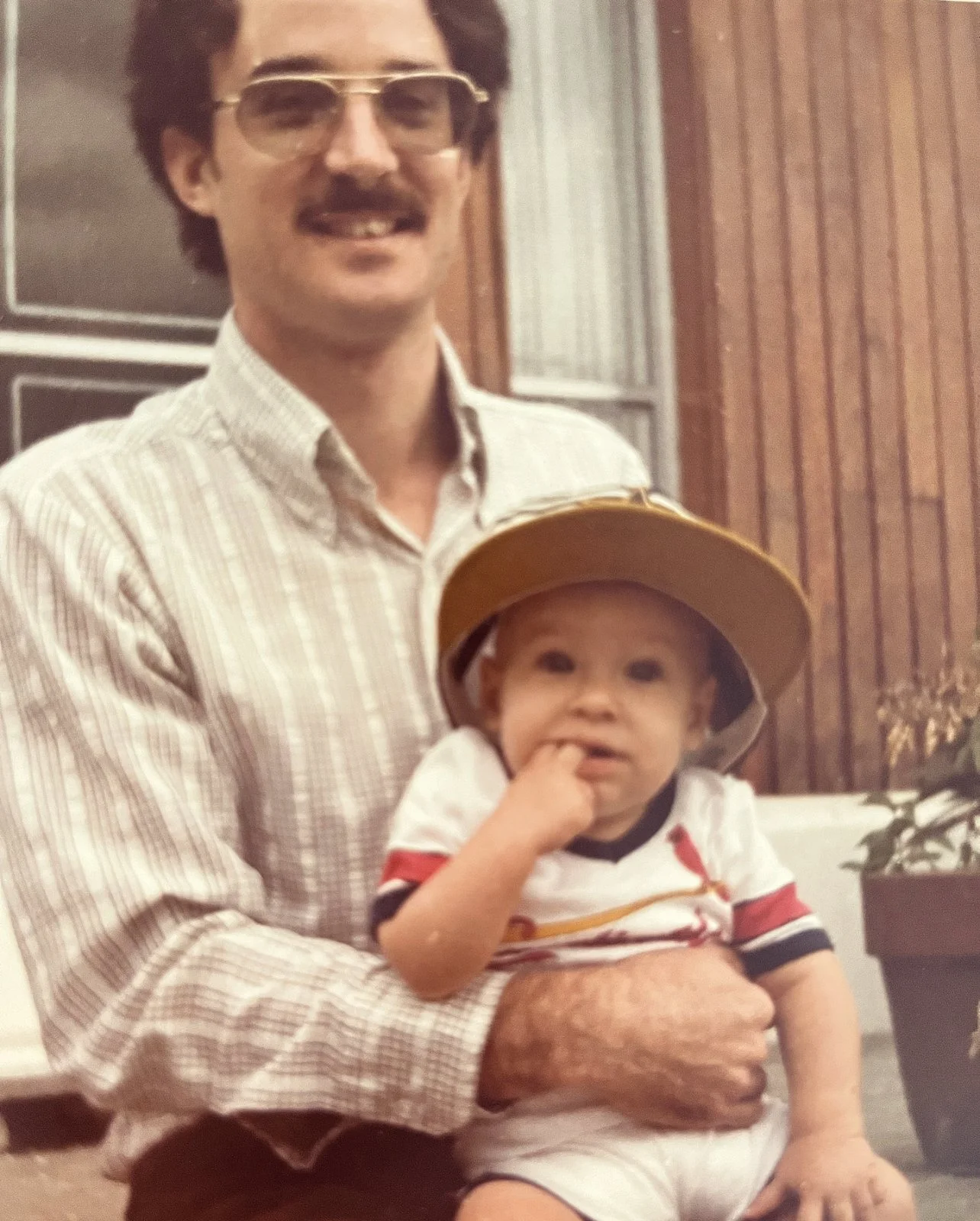

When Bud AKA @DukeFitz AKA Emma’s Dad reaches out and says he wants to write a companion blog to go along with your podcast episode he was a guest on, you say, YES! Especially two days before Father’s Day. For someone who doesn’t like to give advice, he has taught me more than most (and does so writing in the most beautiful prose you’ve read in a long while). Without further ado, my friend, Bud.

Kintsugi is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery by mending the areas of breakage. Rather than concealing the cracks and imperfections, this art form highlights and celebrates them, considering them an integral part of an object’s history and beauty. The analogy perhaps is too on the nose, but it is an apt way to visualize my caregiver journey.

(as an amusing and terrifyingly accurate side note, the etymological roots for the various word parts of ‘caregiver’ come out to ‘one who has to do with bestowing and receiving screams’ and that is just…perfect)

How to be a better support for the growth of those around me has long been the special object of my consideration, and yet, I am hesitant to offer anything more than observations from my own meandering experiences.

Much of the reticence around using my journey as a guide for others comes from the fact that I am still in the midst of the trek. It’s akin to asking a drowning person for swimming advice. Sure, my head is still above water but nothing about my situation invokes in me a sense of confidence or competence in my abilities, least of all at a level where I feel they could be a template for others.

And as I survey the turbid tides of my care structure everyone seems to be drowning. To whom and how am I to speak?

The words we use, how we use them and with whom is more than us just saying something about the world, it is us revealing ourselves to the world. Language is the scaffolding to our house of Being, unconcealing the polished pictures within while concealing the wearied walls they hang upon. And just as there is space between the frames on the wall there needs to be silence in our speaking to allow us to listen to the world around us. In our often unhelpfully talkative culture it seems an affront to devote time trying to know when you must be still and what you must pass over in silence.

I can’t in good faith say you will find joy again after your child’s diagnosis. I’ve known many who have but also many who have not. I can’t say your days will get better any more than I can say they will get worse. I can’t say you will do whatever it takes. I can’t tell you to just keep pushing through life and you’ll make it over the hill. What I can say is the life around you will keep rolling along whether you are pushing or not.

That’s the exquisite catastrophe of this life: it keeps going. The hardest day of my life will pass, but so will the best one regardless of whether I want them to or not.

This isn’t to say I have no choice but to proceed. A common response to the phrase, “I don’t know how you do it!” is, “I don’t have a choice.” Being constantly faced with hard choices can give the illusion of having no choice and in the process steal away confidence and leave fatigue in its place. The advancing degree of hardship doesn’t erode choice but rather sharpens it, brings it into focus. At any moment I could choose to not care for the Kartoffel, to allow my relationship with Maggie to fall into ruin, to leave this earthen plane behind. The obviousness of what I would choose does not remove the fact there was a choice to begin with. Chalking it up to ‘I don’t have a choice’ robs parents who make these choices everyday of a righteous strength they deserve to know they have.

How did these options become so obvious? Because through being the Kartoffel’s dadvocate I have been afforded that rarest of opportunities: to get to know myself.

Life with the Kartoffel has illuminated my existence so as to leave me nowhere to hide from myself. The clearing in the wildwood of our life has had the sublime planted in the muddy messy mixture of grief and joy.

Rather than turning in on myself in our genetically enhanced exile from the beautiful banalities of the status quo, our lives have opened up upon themself, showing all the possibilities that lay before her right alongside the certainties that have brought us to this moment. Instead of bemoaning the world she was born into or the brain she was born with, I'm opening up to the understanding that I get to choose the sort of person I am and then pour that into her days.

It’s been about more than just shifting perspective. It is also more than finding a thing ‘out there’ to fix. It’s a constant reckoning of the granular ‘here-ness’ of our actuality with the ephemeral ‘now-ness’ of our life. It’s about believing that love without reward can have value and bring meaning.

They say you can’t pour from an empty cup, but you can’t fill a broken one either. And, perhaps, for you as well, the golden joinery of your life will be honoring the tears and torrents as much as the smiles and sunshine.

And for Pete’s sake find yourself someone like Kelly who knows how to celebrate the whole person, broken pieces and all.

Kintsugi.

Image description: Bud has dark hair, a beard and glasses and is holding his daughter Emma, who has long blonde hair up to his face. They are facing each other with mouths open in a loving scream/laugh/smile.